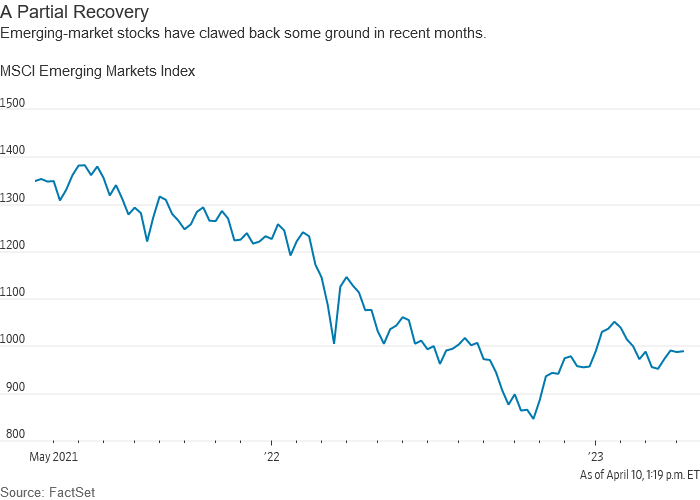

A blistering rally that lifted emerging-market stocks and bonds in recent months may be running out of steam, as concerns resurface about tighter U.S. monetary policy.

The strength of the U.S. economy continues to defy expectations, with data this month showing price pressures remain stubbornly high and the labor market is still strong. That has prompted investors to increase bets that U.S. rates will peak above 5% and stay there for longer, in turn testing demand for investments ranging from Chilean bonds to Thai stocks.

A JPMorgan index of emerging-market bonds has fallen 1.3% this month, while MSCI’s emerging-market stock benchmark has fallen 1.6%. Both indexes last week posted their biggest losses since early fall, while a gauge of emerging-market currencies had its biggest weekly decline since April.

Emerging markets are very sensitive to Federal Reserve policy, because higher U.S. rates make riskier assets comparatively less attractive to investors. Higher rates also typically boost the dollar, making it more expensive for emerging countries to buy oil and other goods that are priced in dollars, or to service hard-currency debts.

“We’re now in that phase where the market is realizing that emerging markets have run quite a lot and that the story in the U.S. is going to go one of two ways,” said David Hauner, head of emerging-market strategy for Europe, the Middle East and Africa at Bank of America. “It’s going to have to either see a sharper deterioration in economic growth, or more Fed hikes.”

Either scenario would weigh on emerging markets in the short term, though the rally will likely resume once the Fed’s policy tightening ends, Mr. Hauner said.

A pullback would continue a highly volatile stretch for emerging-markets investors. They suffered heavy losses last year due to rising global rates, a once-in-a-generation run-up in the dollar and higher commodity prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Then, emerging-market assets and other risky investments began to rebound in the fall as signs of peaking inflation spurred bets that the Fed and other global central banks would soon pause rate increases.

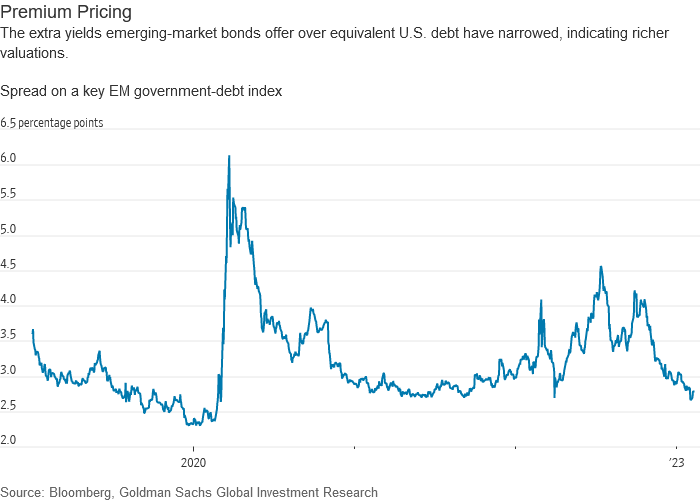

Emerging-market assets will now struggle to rally further because valuations are already rich, said Sara Grut, an analyst at Goldman Sachs. She pointed to the extra yield, or spread, that emerging markets pay to borrow above U.S. Treasury yields. This key measure, which excludes debt from the riskiest governments, has fallen back to prepandemic levels.

“It’s a relatively benign global backdrop. You’re having improving global growth; inflation is coming down,” said Ms. Grut. “All of these things are positive for emerging markets. The challenge for investors is just that a lot of this was already priced in November and December.”

The less-developed world is still generating superior growth. Emerging-market and developing economies will grow by an average of 4% this year, far outpacing a 1.2% expansion from advanced economies, the International Monetary Fund estimated in January.

Bonds from lower-rated emerging nations still look cheap, said Patrick Curran, senior economist at research firm Tellimer. But that reflects the significant challenges still posed to many poorer economies, sometimes referred to as frontier markets, by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

“It’s a tale of two worlds here where large, systemic emerging markets are less vulnerable,” said Mr. Curran. “The opposite is true though for the frontier-market space. There are a lot of countries like Egypt, Kenya, Pakistan, where their external financing needs are huge over the next year, but with yields where they are, they don’t have any ability to issue debt.”

Another headache for emerging markets investors is figuring out what role China will play in the coming year.

Some investors are too optimistic about China’s reopening as a potential driver of growth, said Samy Muaddi, a portfolio manager at T. Rowe Price. That issue, combined with concerns about expensive valuations and inflation, has made him turn more cautious on emerging markets this year.

After both the global financial crisis and its domestic slump in 2015, China supported the domestic economy by encouraging heavy investment in infrastructure and property. That in turn helped prop up global growth, as China rushed to buy up metals from Australia and Latin America, and crude oil from the Middle East and Africa.

While China’s economy is expected to rebound in 2023 after nearly three years of strict Covid-19 policies, analysts expect any stimulus to be more restrained. China is deeply in debt, its housing market is in distress, and much of the infrastructure the country needs is already built.

“In the last 15 years or so, a classical Chinese recovery that’s a more durable driver for emerging markets is accompanied by monetary stimulus,” said Mr. Muaddi. “We’re not seeing evidence of that.”